Escape from Bishkek

Kyrgyzstan feels different to the other Central Asian countries we’ve ridden through. It’s surprisingly better off, evident in the size of the houses, the types of cars and the quality of the (main) road surface. The clothes people wear and the music we hear are more western influenced; we’re much more likely to see girls in jeans and sloganned t-shirts than in long colourful dresses. But there’s also a different attitude. There have been far fewer offers of help or even curious questions about what we’re doing and where we’re going. The 4 year old boy sticking his middle finger up when we first got here was amusing but wouldn’t have happened in Tajikistan. Many people just seem a little stand-offish. Added to the series of unfortunate events from the past few days we’re ready to get going to our next destination.

After a night at the Sakura Guest House in Bishkek we move into the AT House. This is a cyclist’s refuge run by Nathan and Angie who understand exactly what the needs of the two wheeled traveller are. Their garden is laid out to accommodate as many tents as can be squeezed in. There’s a well stocked workshop for bike fettling, a warm shower inside, a cold one outside and an open kitchen for cooking.

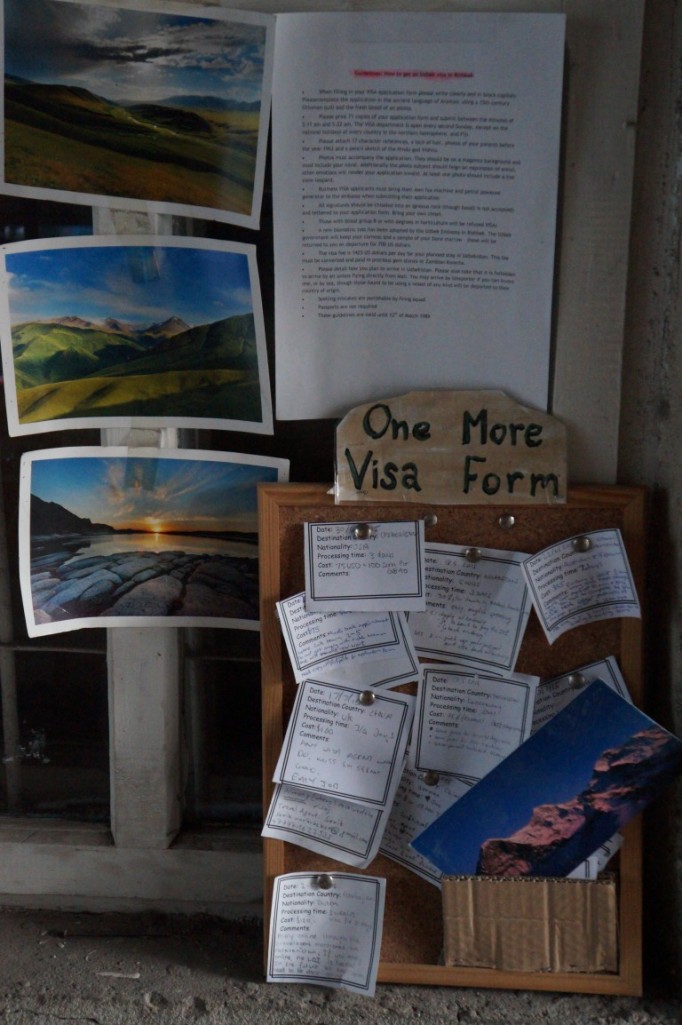

Bishkek is a popular crossroads for cyclists traveling north, south, east and west as it’s the home of several embassies. Visa applications can be made to help with onward travels to China, Russia, all central Asian countries and Iran (for the lucky ones).

The AT House contains several other cyclists who are sat waiting for the tedious beurocratic wheels to turn in their frustratingly slow way, stranded at the mercy of a Consul who considers their application to visit his home country to be the height of inconvenience. Amongst them are Reece and Virgil who are pleased to see us arrive by bike having last seen us leave by bus. We all raise a celebratory glass or two over dinner.

But the following night things get a bit more serious. We hear some popping sounds a few hundred metres from the house that then become louder and more abrupt. We all joke that it sounds like gunfire but then there’s a large explosion and a plume of black smoke climbs into the air. It definitely is gunfire now and then there’s another explosion before it all quietens down again. There are no sirens which seems odd but when Angie and a few others go out to investigate they report that the roads have been cordoned off and there are plenty of police and military vehicles about.

It takes until the following morning before we find any news online. It seems there were some ISIS suspects staying 300m down the road and they were planning an attack on the upcoming Eid festival in the city centre to celebrate the end of Ramadan. The Kyrgyz special forces had found out and preempted the attack with extreme force. Never a dull moment in this country.

A few days after this a tip off from a neighbour about the fact that there are several foreigners staying with Angie and Nathan, many with suspicious appearances, prompts a visit from the police to find out what it’s all about. We’re all asked to show our passports which is fine until they get to Will. His passport is in Dublin awaiting a Russian Visa and all he has to show where he’s from is a crumpled photo copy with a picture of him when we was 18. The police raise a few eye brows as they inspect this proof of id and compare it to the shaggy bearded individual in front of them that is now a prime suspect. He’s marched off to the police station for more questioning, finger prints are taken and he’s given a warning not to leave Bishkek until he has his passport back. As if there was much choice!

Will’s home town has a history of poetry so here’s a few lines to mark his lucky escape from deportation:

Irish Will had a very big beard

Bishkek police thought he looked rather weird

With a city in crisis

They thought he was ISIS

But he wasn’t the terrorist they feared

Like everyone else, our main task in Bishkek (other than avoiding terrorist attacks) is to apply for a Visa. The most popular route from here is to head east into China then down into South East Asia. We’re plotting something a bit different so plan to head further south to take in India, Nepal, Bangladesh and Myanmar/Burma. The two overland routes to get down there are either via the legendary Karakorum Highway through China and Pakistan or via Tibet and straight into Nepal. Visa and security issues make the former difficult (we’d have to send our passports to London and get a bus or police escort for large parts of Pakistan). The latter is impossible without being part of a formal, organised and tightly controlled tour. Annoyingly both options were much easier as independent travelers several years ago but such is the ever changing way of the world.

So we’ve chosen to fly from Bishkek to Delhi. It’s a shame to have to break the overland journey but we feel the benefits from experiencing this colourful and crazy part of the world will outweigh any moral satisfaction we would have felt from avoiding plane journeys at all costs. We make an appointment for the Indian embassy and then have a few days to sort out our other task.

As we’ve come to expect, receiving parcels in foreign countries is seldom straightforward. When I go to claim a package from DHL that my Mum has sent from the UK they tell me it’s being held by customs due to its declared value being over a certain limit. I’m required to go to the airport, 25km away and prove that I’m a cyclist who needs these bike parts and am not going to try and sell them on. A shared taxi ride later and I find myself stood in front of a window where a bored looking man glances at the paperwork for our parcel then glances back at me before giving the thumbs up. That was customs cleared in a few seconds without a single word spoken between us.

Now DHL have to process the paperwork which, despite my protests, can’t be done until after the weekend. A few som passed in a handshake would have no doubt helped the situation but I’m short on cash so I return empty handed and settle for waiting.

Four days after applying for our appointment we get to visit the Indian embassy. No one checks our appointment date and we arrive late but get let in anyway so it looks like the appointment was totally unnecessary. We’re told we can only get a 1 month, single entry visa which is disappointing and a lot less time than we would have got at just about any other Indian embassy. For some reason this one is more stingy. To make matters worse, as British citizens we pay nearly 3 times as much as passport holders from other countries, a tit for tat gesture as Indian residents pay a fortune for UK Visas. With a lot of persuading we manage to get them to at least consider giving us 2 months. All this takes time and as we don’t have enough cash to pay there and then and not enough time to get to an ATM before the embassy closes so we have to return the next day.

Meanwhile the parcel still hasn’t been cleared from customs. DHL tell me it should be at their office today but I go there twice and it it’s still sat at the airport depot.

The following day is much more successful. Back at the Indian embassy, armed with a large wodge of cash we again plead for a more generous Visa. We explain that our plans include ducking in and out of India 3 times to visit neighbouring countries and that because we’re traveling by bike we need more time. The man behind the counter goes to speak to the man upstairs and together they come down and tell us they’ll push for a 3 month, triple entry visa for us. It should be ready by the following Monday too which is half the time we expected it to take to process. As always, if you don’t ask you don’t get!

As there’s been no word from ‘Delivering Hopelessly Late’ I call them and get summoned to their office to claim the parcel at long last. But they still don’t want to give it up without a fight and slap a bill for storage charges on the desk. Storage time that includes the several days that I’ve been desperate to take it from them but haven’t been allowed! I tell them I’m happy to pay but first I’ll deduct my accommodation costs incurred while waiting along with the transport costs paid to run around the city and to the airport. They don’t see the funny side.

I then suggest we go halves just to settle this and after the desk clerk speaks to his manager who speaks to his director we shake on the deal. Only 325 som each (~£3.25) but it’s the principal of the thing that matters.

So what to do with several more days in Bishkek that we’ve now been ‘gifted’ while we wait for the Visa? We’ve already tried the aqua park, visited the state museum (which would be far more interesting if we could read Kyrgyz or Russian), shopped in bike shops, shopped in the huge Osh Bazaar and I’ve had a hair cut and beard trim. The only thing for it is to get out of Bishkek and visit Issyk Kul.

Kyrgyzstan’s number one attraction is a vast lake sat 150km east of the capital and 1000m higher. At 200km x 30km Issyk Kul is the second largest alpine lake in the world and just about everyone we met told us we had to see it.

With us are Irish Will and Korean Kim who we’d met at different points in Uzbekistan and Tajikistan and who ended up riding a lot of the Pamir Highway together. They overtook us while we were without bike in Kara Balta. Also with us are Matthew, a German-Australian and his friend Tim, who had been persuaded to act as a bike kit mule and flown in especially to deliver some spare parts (much more sensible than posting). Matthew is a dab hand with a Go Pro camera so his videos are well worth viewing.

At Balykchy our happy band of campers cram into a taxi and hurtle round the lake to a popular destination on the South shore of Issyk Kul. Here we find a salt lake to float in, a mud lake to wallow in then camp by the main lake for more swimming and a round of Kumis with the family that look after the beach.

The array of cyclist’s tan lines on show amongst our group is astonishing and we all proudly display them like a badge of honour.

The slow train delivers us back to Bishkek late the next day leaving us two more days to fill before our flight to Delhi. Just enough time to write some words for the blog, fit the new parts to the bike (working gears again, hurray!) and eat lots more fresh water melon.

We also pay a visit to Dale and Beth who had provided their address for the parcel to be sent to, even though it never got as far as their house. They had been very kind fielding numerous phone calls from DHL before we arrived in Bishkek. We’d been put in touch via some friends of my cousin so it was a very tenuous connection but very valuable to us and we were keen to show our gratitude in person. They’ve lived in Kyrgyzstan long enough to know about all the various scams and unnecessary complications and give an insight into how it can be a fascinating but frustrating place to live.

The day before we’re due to fly we make a final visit to the Indian embassy to retrieve out passports. When they hand them to us we nervously open them to find a 3 month, multiple entry visa neatly attached inside each one. This produces two big grins as we leave the embassy. Just what we needed!

It’s our turn to send a parcel now as a few things have become redundant and our winter quilt has been replaced by the summer one so needs to go home. We eventually find the main post office and get directed to the Cargo department. In front of a huge map of the world sits a sewing machine and a very busy lady who is grabbing parcels, weighing them and handing over forms. Our parcel quickly enters this process and we have five different forms to fill in. The role of the sewing machine then becomes apparent when she expertly crafts a linen bag for our box to be slotted into. This is then sewn up and sealed with hot wax like an ancient manuscript. Whether the parcel makes it back to the UK is anyone’s guess but the care and attention shown here is impressive so it’s a good start [edit: it took a week with no issues and at half the price of DHL].

Then we’re ready to leave central Asia after nearly three months in countries ending in ‘Stan. Each one has proved interesting and unique in their own way but always with some common connections through the food, language, vodka and the ladas. As an area of the world that is often overlooked and is constantly changing we can’t recommend it highly enough.

At Bishkek airport early the next morning we push the bike into the departure lounge, remove the pedals, turn the bars and cocoon it in polythene and gaffa tape. The panniers go into stripey shopping bags and we join the queue to check in with the usual curious looks at our unusual luggage.

At the desk we’re first told to re wrap the bike using the cling film machine as it may damage the plane. We point out that a few sheets of cling film is unlikely to be better than thick polythene which they reluctantly accept is probably true. They try to weigh the bike by standing it precariously 2.5m tall on its back wheel on the scales. Next they claim we have to pay $150 excess, which is nonsense. A screen shot of their own cycle policy (Air Pegasus) that I had saved on my phone soon reduces this to $40 which again they reluctantly accept.

The first rule of flying with a tandem is to not tell the airline you’re bringing a tandem. Likely as not they won’t know how to deal with the problem so will solve it by saying no you can’t take it. However if you’re there at the check in desk with the bike wrapped and ready to go then it’s much harder for them to turn you away.

The bike disappears through a door and we walk through to airside to wait for the plane. The fate of the rest of the journey now lies with the airport ‘chuckers’ at both ends of our flight. Will it make it to Delhi and will it still resemble a working bicycle? The answer would be at the end of a four hour flight.