Samarkand to Dushanbe

24th May to 5th June 2015

Kirsty was always very proud of her attendance record at her former place of work. In the 14 years she was there the number of days off that she took due to sickness could be counted on one hand. One of those was partly my fault after taking her to a sea food restaurant where she ate a dodgy oyster. We’ve managed to stay fit and healthy for most of the journey so far with just the occasional sniffle to deal with but there’s a certain amount of inevitability to getting sick when travelling for a long time.

Leaving Samarkand we’re both feeling good as we pick our way through some small residential streets on gravel roads and emerge on the main highway that leads to Tashkent. Riding a few km north we arrive at our destination for the morning: the Samarkand Rowing Canal.

We’d always planned to try and do some rowing during the trip if we got the chance. So when I found out there was an international rowing lake in Samarkand I got in touch with Savara at the Rowing and Canoe Federation of Uzbekistan to see if we could go for a paddle. She was incredibly helpful and organised for us to meet the national team coach and borrow a boat.

We roll up to the boat house and get warmly greeted by Manucher. It’s much like any rowing lake with just over 2000m of water, a small grandstand compete with Olympic rings symbol (don’t tell the IOC), and timing booths every 500m. But there are a few things that make it different from Eton Dorney and Holme Pierrepoint in England. In the distance a huge range of white, jagged mountains fills the horizon. Cows graze around the 500m marker and a team of workers are cutting the grass on the bank by hand using sickles.

Manucher shows us our boat and blades painted in the Uzbek national colours and we quickly take to the water. Also in common with most rowing lakes there’s a strong cross wind which makes the paddling a little trickier. But it’s lovely to be out on the water for the first time in 3 years. In fact the last time we were in a double scull I ended up proposing to Kirsty.

After a trip to the end of the lake and back and a few racing ‘bursts’ we’re glad to have stayed upright and dry so decide to cut our losses and head back to dry land.

After thanking Manucher and a photo with some of the national squad we’re back on the bike and pedaling again but we’ll be on the look out for more rowing lakes.

At this point Kirsty admits to be running at about 80%. Perhaps the efforts in the boat took more out of us than we realised? It’s hot and hilly which doesn’t help so we stop for chai and shade mid afternoon and spot a lake in a few km that would make for a good early camp spot.

In the end we settle for a small river instead of the lake and soon gather a gang of interested children who watch closely while we put up the tent and I carry out some running repairs. Meanwhile the shallow river is busy with cars being driven into it for their weekly car wash.

In the morning we’re both under par with grumbling tummies. There’s a 1000m climb ahead of us which we tackle slowly, all the time watching for suitable bushes to hide behind, just in case.

A lengthy lunch at a Chaihana is needed along with a snooze. The great thing about the tea beds is that as well as being a place to drink tea, they are also a bed. In most chaihanas there is someone asleep on one. We’ve also found people sleeping behind the counter in a few shops too.

The hill continues steeply up and we’re ready to stop long before we actually find a patch of flat ground near the top. The one benefit of having to dash out of the tent in the middle of the night is that I get a great view of the milky way overhead.

We finish the climb in the morning and are rewarded with views opening right out to the mountainous Tajik border. This is a new face to Uzbekistan with huge green hills, woods and meadows. Down we go for several bumpy km relieved not to have to exert much energy other than to squeeze the brakes.

The temperature is now 41 degrees so we stop for ice cream as soon as we spot a sign with a range of tempting frozen delights on it, only to find the ice cream machine is broken. The disappointment is palpable.

Pushing on into Shahrisabz the heat isn’t so noticeable while we’re moving. The faster we go, the cooler the breeze.

We were warned by an Aussie in Samarkand that Shahrisabz promised a lot but delivered very little. He was right. There are plenty of ancient buildings of interest but the whole town seems to be a building site surrounded by clouds of dust. I’m sure it’ll all look lovely when it’s finished with some grand landscaping showing off the mosques and monuments but for now a visit to the bazaar for fresh fruit and a swift departure is the order of the day.

Another lengthy lunch stop in the shade of a tree and then a last stint in the cooler, late afternoon brings us to a small gulley where we set up camp. During the evening we watch various groups of animals being led down to the stream for a drink. Even the horses can’t resist as it’s been a hot day for everyone.

We try to get away early to get some riding done before the day heats up. Already there is a busy market in full swing a few hundred metres from our tent. Sheep with enormously fat bottoms overhanging their back legs are being loaded into ladas and mini vans and onto the back of motorbikes. The bigger the bottom the better as it provides more fat for the Lagman/plov/manti/samsa. These animals are the J-Los of the ovine world.

We pass wheat fields and groups of waving, whistling workers. There’s almost a constant barrage of ‘Atkhuda?’, Russian for ‘Where are you from?’ from everyone we meet. After telling them we’re from ‘Anglia’ they seem satisfied and wander off.

The road rises and falls and rises some more. The temperature also rises to 42 degrees and it’s a very dry heat leaving our tongues as dry as Gandhi’s flip flop.

The now routine and necessary afternoon stop finds us next to a stream under a tree. Some children creep out and after the inevitable ‘Atkuda?’ practice their English on us which mostly involves listing types of fruit. We mime the type of fruit in response to show that we understand, much to their amusement.

One of the parents then invites us in and we’re fed a type of delicious milky cheese with tomatoes and sent away with fresh bread.

A steady climb ends the day and we’re joined by a friendly dog who enjoys the view down into a valley with us. He’s happy to finish off some stale bread that we’d been carrying for a few days. Presumably this doesn’t count as throwing it away?

The climb continues through a small dusty village with a police check point on the far side. We’ve passed several of these all through Uzbekistan and have always just been waved straight through without stopping. This time though we’re told in no uncertain terms to stop and present our passports.

We’re given the all clear then it’s brakes off, into the big ring for the rewarding descent. It’s a rocky, red landscape with a few patches of green tucked into the sharp ridge lines. There are huge slabs lent against each other like a collapsed set of dominos.

At the bottom the cliffs close in on us, the road gets rough and we arrive at another police checkpoint. There’s lots of whistling and friendly, perhaps even frantic, waving as we ride on through past the queue of parked cars. They really do seem pleased to see us here.

I stop a couple of hundred metres further down the road to take a photo of an interesting junction and a few seconds later a car skids to a halt alongside. A policeman jumps out and demands to see our passports. We’re then made to ride back up to the checkpoint so they can write our name in what looks like a large school exercise book. I suppose this gives the impression of the authorities knowing where people are throughout the country. There is also a registration system that asks you to collect a stamped receipt for each night a visitor is in country. Fine if you stay in hotels every night but difficult if your accommodation is a tent. We have four receipts for over 3 weeks in the country which causes a lot of shaking of heads and looks of puzzlement. We shrug our shoulders and indicate that that’s all we have, knowing from other people’s experience that this rule is rarely enforced, if ever. Reluctantly they let us go.

So back to that interesting junction we roll. Turning right would take us onto the road to Mazar-I-Sharif and onwards to Kabul. An interesting prospect if it wasn’t for the fact that we don’t have a Afghan visas. Or a pair of kevlar vests. We turn left instead to continue on towards the safety of Tajikistan.

After lunch we endure another very long, hot climb with a bumpy decent on the other side so again no reward for our efforts as I’m hard on the brakes all the way down. While pootling through Baysun an Irish voice calls out to us and another cycle tourist pulls alongside. “You must be Marcus and Kirsty!”. Our reputation precedes us as this is Will who had been riding with Rob and Josh up until a few days ago and had obviously been tipped off that we were on the road ahead of him. He’s staying the night here but we want to go a bit further so we agree to try and meet the next day and ride to the border together.

We’d both been feeling much better for the last few days but the following morning I wake with stomach pains. It eases off once we start riding though so hopefully just a short lived bug from a dodgy ice cream, or the water from a hose or the unmarked bottle of water i’d drunk.

We have a 15km head start on Will and enjoy dropping down into a wonderful valley with a stream cutting deep into the valley floor. There’s a timeless view of a shepherd in a traditional long coat tending to his flock of lardy sheep. Then it’s up and up before a smooth long descent along a ridge with rolling brown hills on either side. It’s nice to be able to let the bike go for once as the road surface is very good.

It looked like we were arriving into a flat plain but after stopping for juice and biscuits and to soak our heads under a cold tap we find its actual very lumpy. A series of short, sharp climbs with just as steep a drop on the other side, sometimes rough and unsurfaced get us working up a sweat. It’s over 40 degrees again.

Lunch with our feet in a stream is a refreshing relief and I’m about to lie down in it when a small snake pokes it’s head above the water, takes one look at us and then disappears. Time to get moving again. But not before a few passersby have given us bread and biscuits.

We don’t get far as we’re distracted by some plum trees and stop to pick some. At the same time a car pulls up to us and a man we recognised as one of the bread and biscuit donors climbs out with his 14 year old daughter. She explains that she is at the top of her English class and wants to practice. She also wants an English pen friend so we hand her our email address but we’re still waiting to hear from her.

Will finally catches us as we’re pulled over once more to receive an offer of chai. The tiny roadside stall sells an eclectic mix of goods ranging from individual cigarettes, to bars of soap, noodles and fizzy drinks.

The two bikes move quickly into Denow where we pick up supplies then navigate our way straight out again. The stomach cramps have returned and Will admits he’s not 100% either so we begin the search for somewhere to hide the tents.

The options are very sparse as it’s all quite built up but we settle for some rough ground next to a derelict building. Not very salubrious as it also seems to be the village tip but desperate cycle tourists can’t be too picky. We’re all a bit despondent as it’s not the memorable last night in Uzbekistan we’d hoped for.

But before we can pitch the ‘palatcas’ we’re saved from a night on the dump by our neighbours from across the road. It appears to be some sort of oil processing depot and they proudly show us their laboratory and bottling shed. Will has a reasonable grasp of Russian having studied it for a few months before starting the trip (putting us to shame) so he’s able to convey our respective stories as well as our needs.

The owner is a Mr Choiyny who happens to be in Germany at the moment so we’re offered his cosy room for the night. In case we’re in any doubt that he won’t mind a phone is presented with Mr Choiyny on the other end. In a combination of German and Russian Will is given the message that we are more than welcome and that his staff will look after us.

A table is brought out followed by several courses of delicious food. Both Will and I have perked up again so manage to gratefully tuck in. It’s a lovely, restful evening and just what we needed to recuperate before the last stint to the border thanks to Mr Choiyny and his staff.

Things are not quite as pleasant in the morning though. Will had decided to pitch his tent on the hard standing and we find him lying on a piece of carpet outside it looking very much worse for wear. He’d had a rough night with an upset stomach and is in no fit state to ride that day. We explain to the oil staff that he needs to sleep and ask if he can stay but to our surprise the answer is “no, clear off”. It’s a compete turnaround after the generosity of the night before. We can only assume that this is due to a fear of being caught by the authorities. It’s actually forbidden for tourists to be given accommodation unless in a licenced hotel or guest house. This is one of the reasons they have the registration process. The nights in Pamela’s and Moyrags homes and also the night here at the oil terminal are actually illegal.

Despite this we’d hoped that Will could have been concealed for one day but instead we have to help him pack and are told there’s a guest house in the next town, just 2 or 3 km away.

4.5 km later we arrive having towed Will as best we can. We’re immediately told there is no guest house which comes as a blow. Our next move is to ask at the nearest Chaihana for some sleeping space and after some discussion with the proprietress a door is opened in a small shed and Will is installed on the mattress inside. We stock him up with water and crisps and he insists we carry on without him. All being well we’ll see him again in Dushanbe the day after.

The run up to the border takes us closer to the huge mountains we’d started seeing since leaving Samarkand. We stop to pick wild cherries by the road side and then again to let a huge heard of horses come galloping along the road.

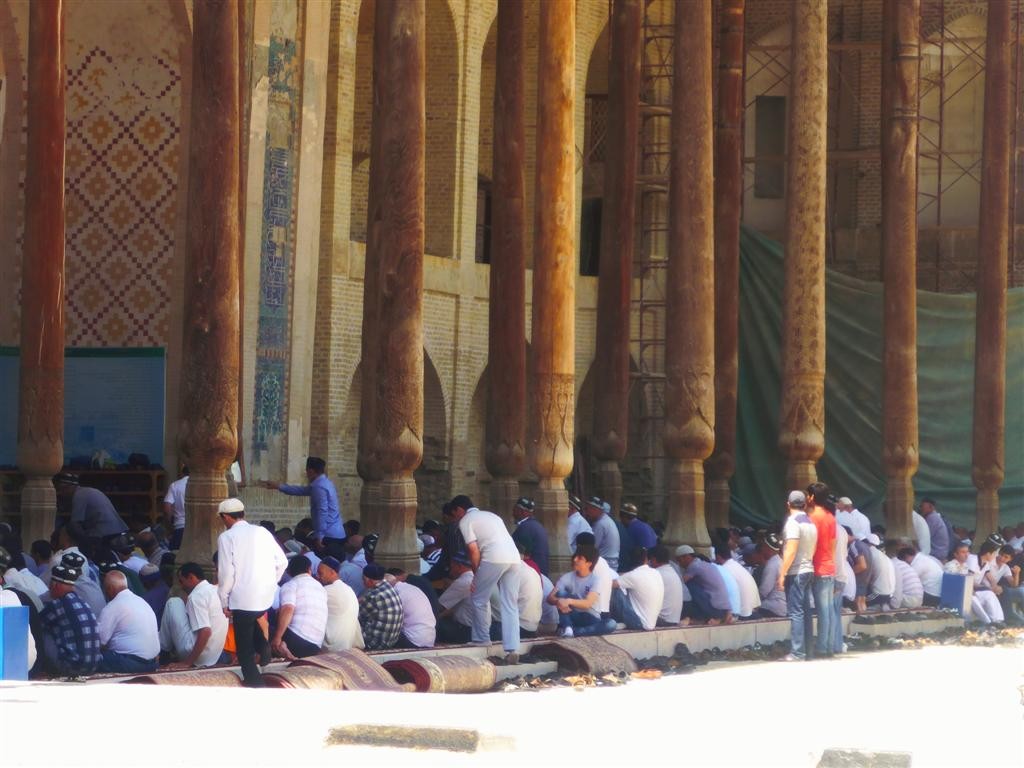

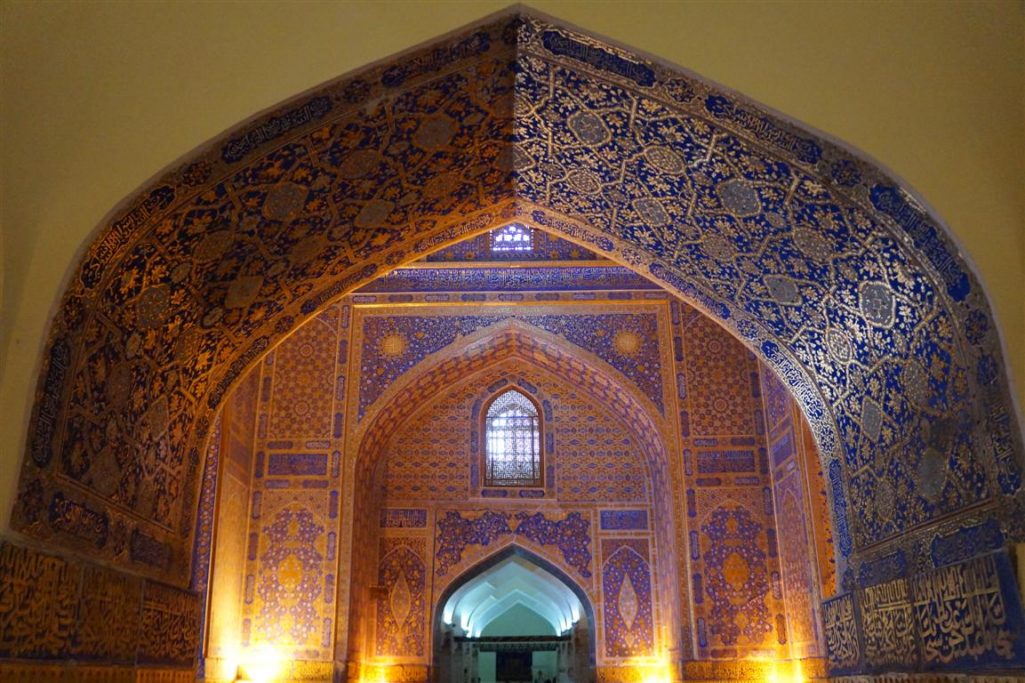

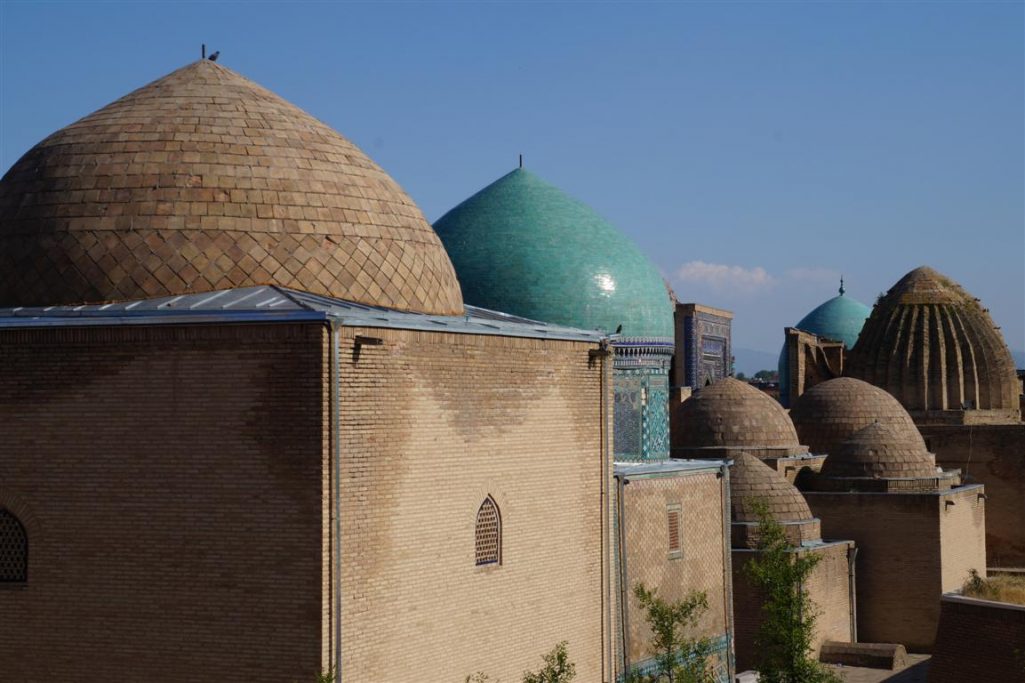

We’ve now ridden the entire length of Uzbekistan and it’s been quite a journey full of colourful characters, spontaneous generosity, interesting history and wonderful landscapes. But mostly desert.

Standing in the customs office we’re a bit nervous as we don’t have the declaration form that was supposed to have been given to us on entry (we managed to skip that on the way in from Kazakhstan). Their main concern is movement of foreign currency so we declare that we have $25 and there doesn’t seem to be a problem. However they then start a search of our panniers diving deeper and deeper into the murky depths, opening tins and rummaging through our medical kit. When the customs officer reaches the oily tools and spares section she rapidly loses interest and tells us to repack as we’re free to go. But not before a quick body check. For the second time in my life I’m told I have ‘very strong legs’ after a squeeze by a customs officer. I’m not sure whether to be flattered or disturbed.

At the passport control there’s more shaking of heads at our lack of hotel registration slips but we get the ink on the page and push off in the direction of the Tajik border control. Luckily the $200 concealed about Kristy’s person was not found.

Up a hill (we’d better get used to this) we quickly meet the Tajik guards, fill in a form with no apparent purpose and have our temperatures taken as a cursory health check. Given the all clear we’re released into Country #29: Tajikistan.

The smooth processing at the border is followed by a smooth road all the way into Dushanbe, the capital and also the Tajik word for Monday. This must cause some confusion.

-When are you going to Dushanbe?

-Dushanbe.

-Yes but when.

-Oh, I’m going to Dushanbe on Dushanbe.

-??

Another Warmshowers legend is waiting for us in the form of Véro. There can’t be a single cyclist travelling through Tajikistan who doesn’t pitch their tent in her garden and when we arrive there are another 8 people staying from Hungary, Belgium, Germany, America, France and Taunton. Véro moved here from France 2 years ago to work for the EU and has since opened her house as a peaceful refuge in the middle of a busy city.

We need a few days to compose ourselves for the next leg of the trip as it’s going to be a tough one. For the flattest part of the Kyzyl Kym desert we climbed just 1,200m over the course of 1,200km. Up ahead we have the Pamir highway with 20,000m to climb over a 1,200km distance and some very high altitude passes.

It’s not as if I’m in a hurry to go anywhere anyway as my stomach is still complaining about something I put into it. Everyone in the house who has arrived from Uzbekistan has had similar troubles so it seems like a standard parting gift.

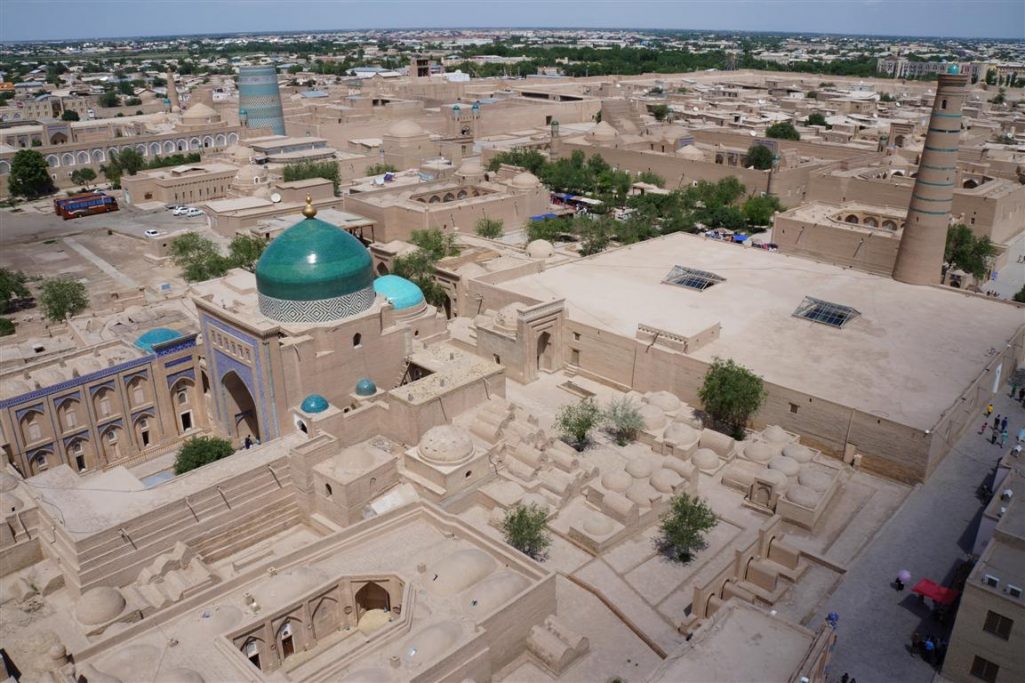

We have a couple of tasks to do while we stay in the city, the most important of which is to apply for a permit to enter the Badakshan Autonomous Region (GBAO) that encompasses the Pamirs. We’d had a fright in Khiva when we’d been told by some other cyclists that permits were no longer being issued. Apparently the pesky Taliban had been trying to ruin things for everyone by coming too close to the Afghan/Tajik border so the Tajik government didn’t want tourists going that way. Luckily they’ve now been pushed south so it’s deemed safe again and permits are available again. It takes a day and 20 somani (£2) to sort out the vital slip of paper to allow us to get into the mountains.

On one evening we’re invited to join a party at the home of some Americans. They are US Special Forces celebrating a changing of the guard as one group leaves and another arrives to take over. We get an interesting insight into their work training Tajik soldiers (all highly classified) but quickly the party degenerates into a cross between American Pie and Team America with a highly realistic wrestling match towards the end. Their work over here has been slightly tarnished with the recent defection of the Tajik head of police to ISIS, taking with him a lot of the training and information given to him by the US Special Forces. Let’s hope the new lot have more luck.

Will did arrive the day after us after a harrowing experience in the Chaihana. In the traditions of his home town here’s a Limerick to tell the story:

There was a young man called Will

Who while cycling felt really quite ill

At a tea house he rested

And his composure was tested

When he was offered much more than the bill.

He was even more glad to reach the safety of Véro’s garden than most.

After four days in the tranquil surroundings of Véro’s garden (apart from the screeching peacocks from the adjacent presidential palace and Véros talkative, whistling parrot) I’m feeling 90% well which is enough for me to want to get going.

It would have been easy to stay longer (the record is one month) but on a sunny Friday afternoon everything returns to it’s rightful place in our panniers and we head out onto the road again. Hopefully we won’t have too many more off-days to detract from our attendance record.